South Dakota

Our Badlands cabin window faces east. Abby and I wake to a gorgeous sunrise over this foreign landscape.

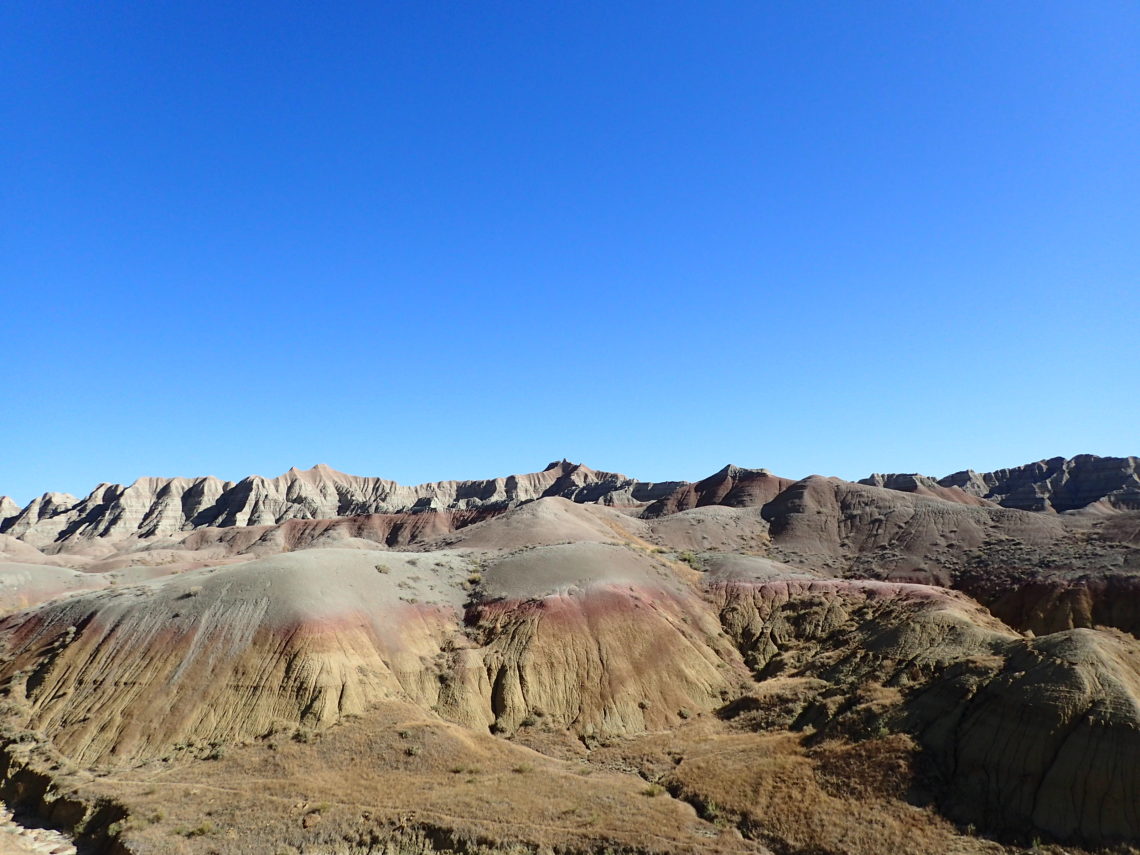

It features sharply eroded buttes, pinnacles, and spires that blend with the largest protected, mixed-grass prairie in the United States. Wind and water have ruthlessly ravaged this unique region. Rich bands of color stripe across the rock faces and reveal different eras of time, reinforcing that the Earth is an always evolving and dynamic system. “The Wall” is the largest badlands feature. It is a 60-mile stretch of tens-of-millions-years-old rock that acts as a barrier between the upper and lower prairies.

The Lakota people, part of the Great Sioux Nation, refer to the harsh environment and rugged terrain as mako sica or “bad lands.” They work with the National Park Service to protect the south unit of the National Park, where they have lived for 11,000 years. You feel their influences in the park, like my delicious breakfast of Sioux Fry Bread with berry compote.

The Badlands is a sacred place. The Lakota performed the last ghost dance in December 1890 at Stronghold Table, a grassy bluff about 30 miles south. In a time of the aggressive implementation of the reservation system, assimilation programs, and tragic massacres, the Ghost Dance provided a spiritual language of resistance. Participants held hands and danced around in a circle with a shuffling side to side step, singing and swaying. Ghost Dancers seemed more defiant than other Native Americans, and the rituals seemed to work its participants into a frenzy.

In 1890, local residents of South Dakota demanded that the Native Americans at the Standing Rock Reservation end the ritual of the Ghost Dance. When they were ignored, the United States Army was called for assistance. A group of over 300 Lakota men, women, and children tried to reach safety at the Pine Ridge Reservation. They were detained by United States Army at a creek called Wounded Knee and held at gunpoint. The men were separated from the women and children. As the soldiers confiscated weapons from the men, a deaf man refused to give up his rifle, it discharged, and the shooting began. Estimates say approximately 300 Indians were killed, many of them unarmed women and children. The Army lost 25 men. This is embedded in the history books as the Massacre at Wounded Knee.

The Badlands’ animal population is diverse, but I saw only sheep. The Audobon bighorn sheep were a mainstay in the Badlands ecosystem until their extinction in 1926 from over-hunting. Their close relatives, the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, were introduced to the area in the 1960s. Their population grew to near 200 in recent years. Bighorn sheep are at home in the terrain of the buttes of the Badlands because of their excellent ability to climb and scale rocky heights.

The largest mammal in the park is the American bison, the iconic symbol of American wildlife. It’s pictured on the National Park Service insignia. The bison once roamed the Badlands in huge herds. However, by the 1880s, over-hunting made the bison extinct in the area. They were reintroduced in the 1960s. The park service closely manages the bison herd to avoid common diseases, and currently numbers near 450.

An hour drive separates the Badlands from Custer State Park. One of the nation’s largest state parks, Custer is a world-class wildlife refuge and has been recognized on the Ten Best Wildlife Destinations in the World. Abby and I follow two of the most popular scenic drives- Iron Mountain Road and Wildlife Loop Road. Collectively, these roads are a part of the Peter Norbeck Scenic Byway which has been named as one of Ten Most Outstanding Byways in America. A masterpiece of artistic engineering, this 70-mile road includes spiraling bridges, hairpin curves, granite tunnels, and awe-inspiring views. And yes, here we see bison!

To increase tourism to South Dakota, historian Doane Robinson conceived and raised funds for the Mount Rushmore National Memorial. It is a mountain sculpture by artist Gutzon Borglum. The 60-foot faces of America’s most prominent US presidents, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, represent 150 years of American history. This shrine of democracy features the presidents who represent the birth, growth, development, and preservation of this country. You can drive around to the side of the monument for the profile view, which was my favorite. You can also view the tiny faces from a very distant lookout point in Custer State Park. My least favorite is the usual head-on representation.

You May Also Like

Abby

January 8, 2018

The Best of Colorado, Utah and Arizona

January 16, 2018