I Love You Too

Resident Stories

As I leave Sister Margaret’s room, she asks if she can bless me and I say “Yes, of course.” She bows her habit-less head and extends her arms with palms out, and says, “I hope nothing hurts you, no accidents befall you, and you get all that you want, my baby.” I smile at the blessing brought forth from years of clerical repetition and the “my baby” brought forth from her dementia. I bow in thanks and move on in my cloud of heavenly protection.

A husband and wife share a room on the dementia unit. I knock and enter to see him watching either Golden Girls or The Price is Right on volume 60. His wife is sleeping in her bed by the window. According to their charts, he has dementia, but she doesn’t. She must have chosen to stay with him on his locked ward. I explain that I am the eye doctor and he is confused. Lifting her head from her bed, she says “It’s ok, Fred, she is going to look at your eyes.” As I spend the afternoon on that wing, I watch the woman be a caretaker for many of the residents, helping with puzzle pieces, picking up dropped utensils, stopping to ask how one’s family is. Her knowing, weary eyes give away her secret of cognizance and set her apart from the other residents on this wing.

On the next floor, two women are holding hands, peering out a window with their heads together, and their butts in their wheelchairs. As I enter, I say loudly, “What are you ladies looking at?” One says, “A man. We’re old gals but we’re healthy.” I laugh with them. After I examine each of them, I stand to the side, writing their charts. Their lunch is delivered. I eavesdrop on their conversation. They are talking in turn, back and forth, and it would seem that they are talking to each other. In reality, they are having completely separate but parallel conversations. They can’t hear each other, so one woman is talking about the onions in her salad, while the other discusses her son being in the military. “Yes, there are too many onions in this salad.” “My son is stationed in Afghanistan.” “I don’t even like red onions.” “He hasn’t been home in 18 months.” “They are just too spicy for me, I am going to pick them off.” “I want him to come home and give me grandchildren.”

The next resident is barricaded in his hospital bed, with a wheeled table in front of him, a wheelchair to the left of his bed, stacks of books on the floor to the right of him, and curtains pulled around his bed. After our introduction, he asks where I live and I tell him. He shares that he used to live in Philadelphia too and that his boss bought him a huge house and 3 cars. Surprised, I say, “Wow, you must have been a great asset to your boss.” He tells me a little more about how generous his boss was. Then, he asks me what time it is. I look at his clock and it says 4:30 pm. It’s 9:30 am. The clocks are always wrong. He wants his lunch. Later, the staff informs me that his boss was an infamous mob boss in Philadelphia. My patient was his enforcer.

The next room has a sign on the door that says, “Please knock and wait for a response before entering.” I comply and am greeted with posters on the walls. The photographs are of oiled, shirtless, beefcake men. There is also a poster of Tom Selleck sporting his classic mustache and no shirt. The resident is 93. The TV is on and I ask her to turn it down. She yells, “What?” In my first week, I wondered how anyone could stand the noise in these homes. Now, I am immune to it. There are call buttons beeping, repetitive buzzers, loud monitors, always in different pitches, volumes, and tempos. The TVs are always on full blast. The staff is deaf to it in the same way the patients are deaf to our requests for more health monitoring.

I continue to the next resident’s room. She stands next to her bed in her housecoat. I explain to her what we were doing. She says in broken English/Spanish, “I need to put a bra on.” And she proceeds to take off her housecoat to bare breasts. Completely nonchalant, she looks me up and down and says, “You have such a nice figure- tall, thin, firm breasts.” The scene from Sixteen Candles comes to me where the main character’s grandmother remarks “she’s gotten her boobies.” I blush, giggle, and quietly back out of the room stuttering about giving her time to get dressed.

A very obese woman in an extra-wide wheelchair asks me if I can take a joke. I respond, “Sure!”, expecting that she is going to comment on something I said or something wrong about my appearance. She says instead, “What is six inches long, has two nuts and you can hold it in your hand?” She couldn’t even wait for my response as she was so excited to tell me the punch line. “An Almond Joy.”

Another woman tells me about her 80th birthday party that the nursing home threw the previous evening. She describes a man who came into the party, ripped off his clothes, and danced for them all, ” Yes”, she says, “They got me a stripper. Can you believe it? It was marvelous.” This patient comments on the logo that is on the back pocket of my scrubs. When I turn around to get some drops off of my cart, she grabs the logo and, consequently, my butt. She laughs. Later, a nurse pulls me aside to tell me, to be clear, there was no stripper.

There is a handwritten sign in one room “Please leave on Country 100.5, Mom likes it.” The patient is comatose, but that sign is a reminder that there are people who love her outside of this room. The nursing home staff is often in their early 20s and responsible for brushing the resident’s hair and grooming their nails. The patients don’t enjoy the young music preferences, but they do seem to like it when they try new hairstyles or nail art on them. Sometimes, the residents have 2 pigtails, a head full of braids, or a ballerina bun on top of their head. Their nails might be neon, with polka dots, or each painted a different color. Sometimes, the residents sport temporary tattoos. The dichotomy and connection between young and old is heartwarming.

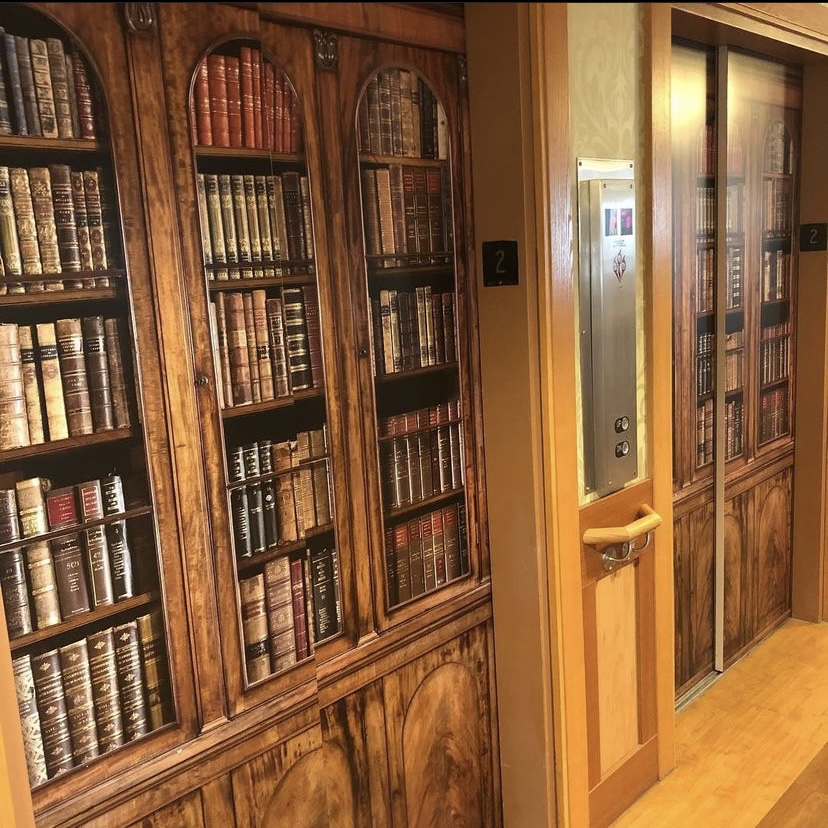

The dining room has an eerie feel. Usually, there are no chairs. There are only blank, empty tables and a sticky floor. It is easier to permanently remove the chairs, as the room will be filled with wheelchairs when it’s mealtime. I overhear conversations here. “Tomorrow, I am going home tomorrow.” “When are you going home?” “I am packed to move back home.” This is not usually the case but it’s often discussed. Also, “Is it time for the bus?” “When is the bus coming?” Some nursing homes build fake bus stops in the hallways to keep residents content and not trying to escape. They just sit and wait for the bus. The homes will also paint the elevator doors to look like library books so the exit route is not so obvious.

Intimacies

The relationship between me and my patients is one of intimate, yet anonymous strangers. They are usually in bed and at least partially undressed. I know their diagnoses and why their leg was lost. Their chart tells me that they were found living in a dumpster and that they were addicted to opioids. I know if they had cancer and all their medications, including anti-depressants, HIV therapy, and constipation suppositories. They are often asleep and I wake them with a gentle shake and an unfamiliar face. There are personal letters on their rolling bed tables and the room smells like sleep or urine or feces. There are pictures on the walls, sometimes showing a brain-dead patient’s former life as a college professor. The question “where are your glasses?” leads to me going through their drawers of underwear, diapers, and toothbrushes. From their standpoint, I walk in as a stranger whom most have never seen before.

Please help these people by getting vaccinated. This request is not about you. This is not about politics. This is about protecting the weakest members of our society and sheltering the least common denominator. The end of life brings humility and a loss of ego. They aren’t afraid to say “help me” because they have no other recourse. This is one way you can help our elders.

One last story.

I examine a 100-year-old woman. I put drops in her eyes and she says, “Thank you!” When I take the pressure in her eyes by bouncing a probe off her corneas and she says, “Thank you!” I blind her with bright light to look at her retina and she says, “Thank you!” When I leave her room after the exam, she calls out after me, “I love you!” I stop. I love you. Residents say this to me so so so many times, maybe it’s a brain glitch back to when their children left home, saying “I love you” as a goodbye. Maybe they mistake me for a neighbor, sister, mother. At first, it felt weird to say, “I love you too.” My honest self questioned if I could respond with sincerity to a stranger.

The longer that I am an eye doctor to the elderly, I yell back with more and more gusto. “I LOVE YOU TOO!

You May Also Like

Happy Birthday, Mom!

August 12, 2018

The Moment I Knew

October 13, 2021

16 Comments

Rachel

This was sooooo good! I laughed out loud. Despite what I’m sure are daily complexities, I think you are kind of a lucky lady to have this job with its vantage point.

marhiggins

Thank you for your kind words. Unexpectedly, I do love it! Thanks for reading!

Paula Katona Davis

Maria, your story is beautiful! You not only provide your professional services but also your compassion and friendship to these beautiful and colorful human beings!

marhiggins

Thank you for your kind words. “Colorful” is a perfect way to describe them. And thanks for reading!

Erica Hacker

Now I want an Almond Joy.

marhiggins

You made me laugh out loud!

Douglas Zaruba

Maria,

Your time in Frederick was far too brief! I wish I had the chance to know you better. You are probably the most interesting person I know. Thanks for being you.

marhiggins

That is one of the nicest compliments I have ever received. Thank you for saying that and for reading!

Tressa Malikkal

Maria, this is so touching! So amazing to connect with all these patients have a whole life time of stories. You are truly a blessing. You are a part of their last times on this earth.

marhiggins

Thank you, Tressa. You are too kind.

Gail Cassidy

Your words draw pictures and sounds and feelings and conversations, and I end up smiling, then laughing, then crying! Beautifully done!! What a difference you are making in their lives just by your presence and your caring! WOW! WOW! WOW!

marhiggins

I appreciate you so much. You have taught me so much. Thanks for being such an amazing mentor, for your comments, and for reading!

Donald W. Swanson

I always enjoy reading your stories! Thank you for sharing them!

marhiggins

Thanks for reading! I hope to be more consistent in the future. Hope you are well!

Uncle Mike

I am sure Aunt Patti can relate to what you are saying ere

marhiggins

Yes! She commented that it reminded her of her days in the nursing home. Thanks for reading.