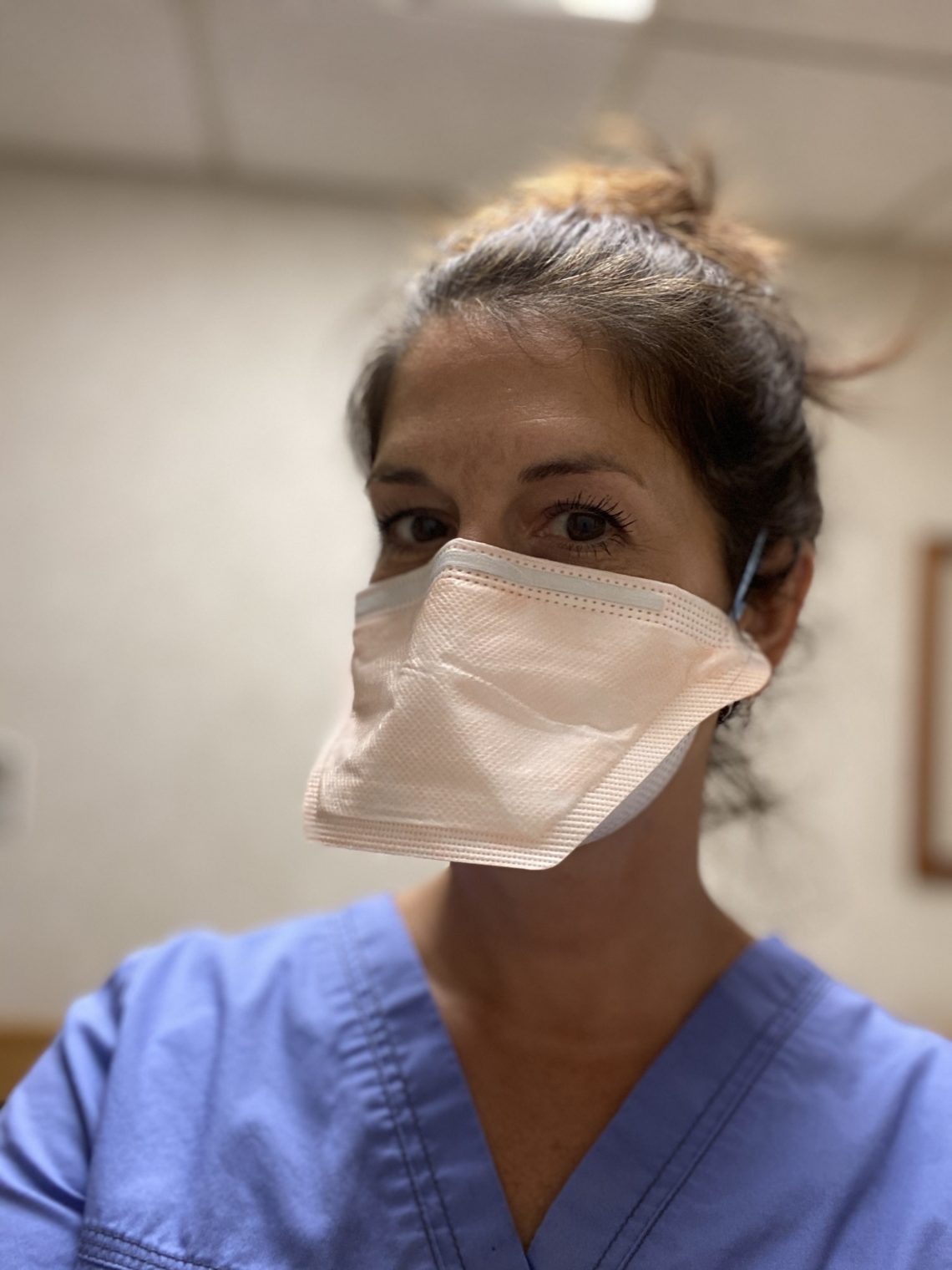

Mask it.

Welcome back.

It’s my first week back after three months when the nursing homes locked their doors to everyone but truly essential personnel. I unload my car — foldable cart first, then luggage that stores ophthalmic equipment. I find my N95 mask, pull my hair up on top of my head, and secure the mask elastic around my bun. In addition to a mask, this home requires a gown, face shield, and gloves. I stop at the front desk where they take my temperature and ask the usual COVID-related questions. I answer yes to the question, “Have you visited another facility with COVID patients?” Knowing that it’s the nature of my job, and because I get tested weekly, they let me in anyway.

My first stop is the social worker’s office. I check with them, seeing if my patient list is still valid. The staff scans my list, crossing off those who have passed away, who is out at the hospital, and who is in dialysis. They inform me of any unusual personality quirks of those who are memorable.

At the start of the pandemic, many staff had COVID. They developed an attitude similar to a seasoned parachuter contrasted to the innocence of a first time newbie. Having come out on the other side, uncertainty and fear are gone and that creates subtle confidence.

Residents

Before I head to the resident’s rooms, I peruse their charts. I look through their diagnoses list to see if they have diabetes (the leading cause of blindness), hypertension (a common reason for blood vessel changes), high cholesterol (a common reason for clots in the ocular blood vessels), take blood thinners (a cause of bleeds in the eye), or any eye drops. Now I also note if they have survived COVID. On one notable chart, the typed word “married” is crossed out in pen and “widowed” is written next to it.

Before the COVID quarantine, maybe 5-10% of patients would refuse an exam. Some with a snarl, some because of sickness, some couldn’t verbalize their displeasure but would communicate with a refusal to open their eyes. Now not a single patient refuses an exam. The residents are starved for attention from someone other than their usual nurses. As I walk in their door, they blurt out, “I fought in the Korean War, four Purple Hearts!” Or “I have eight kids; they’re all very successful.” Or “My wife thinks black glasses make me look handsome!” Or “Do you have food on that cart?”

To break up the weight that sometimes presses on me, I try to add some humor and lightness. One home gives me an N95 mask with a bill that looks like a duck. I send a photo to my niece. Patients laugh at that mask too. I laminate a photo of myself and my dog and pin it to my scrubs. Patients can see my face and they always comment on Abby. It brings a smile and a story about their dogs.

I don’t know my patients well. At one point, I visited over 50 homes in five states. I spend 15 minutes total with each patient, seeing 100 patients a week. This arrangement doesn’t allow me to dig too deep into their personal lives. But some residents stick with me.

The Wilsons

The Wilsons have been married for 63 years. They are a white couple with six kids, whom they haven’t seen in person in months. Their shared room has two twin hospital beds separated by a two-foot aisle. Pictures cover the walls – family, kids, vacations. Trinkets like knitted afghans and a small book collection smell like their old home. Memories of a lifetime are condensed into a 10×16 foot room. Both Wilsons had COVID in March, and they emerged frailer and more disoriented.

Mr. Wilson carefully pushes Mrs. Wilson in a wheelchair out of their room and they start to walk the halls. They are giddy that they are finally allowed to leave their room. He leans over the back of her chair, using his weight to propel them forward and using the handles for stability. He has a shock of blonde grey hair falling over his eye as a consequence of barbershop services being suspended. Mr. Watson absently pushes his hair back and it falls in the exact same place again. He looks like a boyish but elderly surfer.

A young male staff person stops them to remind them to put on their masks. Mr. Wilson is confused for a moment, either he can’t remember what a mask is or he has forgotten why he needs it. The staff person goes into their room, grabs 2 masks, and hands them to him. Mr. Wilson leans over and gently wraps the mask elastics around Mrs. Wilson’s ears, saying, “Mother, you need your mask.” She looks at him with blank eyes but complies without complaint. After assuring she is comfortable, he puts his mask on, ignoring the universal airline recommendation to put your mask on first. Slowly, they wheel down the hall.

Edith

Last year, I examined a patient who was very frail, lying in bed, pale and shaking. The nursing homes are always hot, heated to the comfort of the elderly, which is about 80 degrees. Her shaking wasn’t from the temperature. I adapt my clothing to be the coolest, wearing just scrubs, no shirt underneath, no sweater on top, with my hair pulled off my neck into a messy bun or a ponytail. I lean over her bed to shine a light in her eyes to check her pupillary responses. She startles me by opening her eyes wide, reaching up, grabbing my ponytail, and pulling hard. She is freakishly strong and cranks my neck to the side with her might. I wrap my hand around her wrist and slowly pry her fingers from my hair.

Recently, I visit her again because she broke her glasses. She sits on the edge of her tiny bed, with disheveled sheets, still shaking from her neurological disorder. I don’t remember that she is the ponytail puller until halfway through her exam. I proceed more cautiously. After all the tests are over, I tell her that her new glasses will be mailed to the home in 2 weeks. She gazes deeply into my eyes, with tears glazing hers. Standing as quickly as she’s able, she leans into me and abruptly hugs me. I hold her small frame for a moment while she cries. Then, she pulls back and says vehemently, “Thank you.” I brush it off saying, “Oh, anytime, anything for you.”

As I turn to leave the room, tears sting my eyes. Her gratitude and warmth touched me. But also, being single and living alone, it was one of the few times I had been hugged in the last three months. A hug from a previously combative stranger felt beautiful and emotionally overwhelming.

Darlene

I have a nurse review my patient list for her first-floor wing. She points to one name, “Darlene”, and says, “She’ll give you a hard time.” I say, “It’s ok, I’m used to it.” I move Darlene to the top of my list and drag my cart behind me to her room. As I enter, a nurse is sitting with Darlene and talking on the phone. She mouths to me that now isn’t a good time. The nurse points to the window and says, “Darlene’s son and granddaughter will be visiting in a moment.” I say, “No problem, I’ll come back.” As I maneuver my cart to turn around, the nurse stops me with “Wait! Maybe he can help.” I complete the circle and face them again.

A man’s silhouette appears at the window, with a smaller, shorter outline to his side. Darlene exclaims in joy because through her dementia, she recognizes him. More quickly than I would have imagined, frail Darlene is at the window, pressing her tiny hands to the glass. She exclaims a mix of love, sorrow, pain, and relief. The noise she makes sounds like a wounded animal who sees help coming. It hurts my heart.

Darlene’s son places his hands on the window outside covering her prints. She paws and pets at his hands, trying to make the half-inch glass between them disappear. Darlene puts her face right up to the window and says, “hello hello hello hello.” The nurse gives her the phone which is already connected to her son. He talks to her soothingly and she hugs the phone with the crook of her neck, squeezing all the connection she can from the receiver. If he feels pain because of her condition, he masks it with love.

I give them time to reconnect before I explain why I am standing there watching them creepily. Her son tells me that he bought her glasses at Boscov’s and that he picked them out himself. His face shows slight embarrassment as he says that he didn’t have her with him to fit them, so they are a little large. I reassure him that he did a great job and that they fit surprisingly well without her trying them on.

With him on the other side of the window, Darlene allows me to put drops in her eyes and fit her for new glasses. She is extremely nearsighted and I want to make sure she has a spare if her current glasses go missing again. The effect of her son’s presence and my association with him lasts until 30 minutes later when I return to check her dilated eyes. She is compliant, peaceful, and happy. She waves goodbye when I leave.

Jacqueline

I knock on the door to the room of the next patient. I hear a high-pitched “Come in!” The white woman in bed D (for “door”) is lying on her back with her limbs bent and distorted at strange angles. She has contracture, which causes this unusual appearance. Medical contracture develops when the normally stretchy, elastic tissue is replaced by non-stretchy, inelastic, fiber-like tissue, and prevents normal movement.

She is also completely topless, and only a thin sheet covers her diapered bottom half. I am more shocked by the lack of a shirt than the contracture, as contracture is common in my patients. As I enter, she moves her twisted arm to poorly cover her breasts. Her response is more instinctual than necessary. Her breasts aren’t easily distinguishable, as she may have had a mastectomy. I ask her if she would like me to cover her. She says, “Honey, my thermostat is off, I am always hot. If it doesn’t bother you, it doesn’t bother me.” I confirm that I’m not concerned.

After her exam, she asks me to dial her cell phone. I do. Then, she asks me to place the phone on her bare chest, as her hands are too distorted to hold it. I do. I ask if she’s ok before I leave the room. She is. As I walk down the hall, I hear her proclaiming, “Hey! Guess what? I was outside for a whole hour yesterday! It was so wonderful…” Her voice fades as I get further away.

Gerard

Next, a 36-year-old black man, dressed stylishly in a black tee-shirt and converse sneakers with the laces undone, is sitting in a wheelchair. He explains that he had fluid buildup on his brain from trauma and that his vision has been bad ever since. He looks at me straight with his left eye, but his right eye is about 45 degrees off-center, looking off to my left. I ask if he sees double, which is a common complaint when eyes are misaligned. Luckily, he doesn’t. He happens to be sitting in a private hallway, so I do his exam there.

As I am checking his retina, my view suddenly flies away. I look under my headpiece at his face and his eyes are following something down the hall. I look in the direction of his gaze and spy an attractive nurse with hair down her back wearing tight scrubs. She tosses a “Hi, Gerard” over her shoulder. He smiles slyly. I tap him on the forehead, as my hand is still holding the magnifying lens above his eye, and joke, “Hey. Two minutes, two minutes is all I need. Stop staring at the pretty nurses.” He giggles and looks at me again with a satisfied grin.

Malachi

The next room is completely dark and a patient is sitting in a wheelchair by the window. He is the last person on my list. His chart says he’s 48 years old and blind in both eyes. I introduce myself as the eye doctor and he is excited to hear that I am going to look at his eyes. I direct my penlight at his globes, searching for his pupils. There is not much to examine. One eye is phthisical and the other eye has a complete corneal scar. Phthisical means that the eye sustained damage, shriveled within itself, and has become shrunken and completely cloudy. I have no view into either eye and consequently, he has no view out.

When I measure his visual acuity, we begin with the eye chart on my phone, calibrated for my four-foot arm span. He can’t see the largest letter, which is 20/400. I ask if he can count my fingers at four feet, then two, then one. He replies no every time. I use my penlight and ask him if the light is on or off. It is on. He says, “off” with conviction. He is NLP, no light perception. Black is all he sees.

He asks me over and over and over if I can fix his eyes. Is there surgery? Are there glasses that can help? Anything at all that I can do? Repeating myself, trying to use different words each time, I explain gently that there is nothing that can be done to make him see again. Each hopeless repetition becomes more painful for me. I can’t imagine how the hurt escalates for him.

Mask it

In Maryland, there is a home where I saw patients in 2018 and 2019. That home had a total of 87 coronavirus infections and 28 deaths among the residents. In one day, 66 of its 95 residents tested positive. In addition, 18 staff members contracted COVID. The overall death rate was 30%. The rapid spread was attributed partially to not wearing masks.

All of these patients have a diagnosis list of 10 or more co-morbidities. Ignore ego and disregard politics. Wear your mask because it’s the right thing to do.

The man in the grocery line behind you could be the Watson’s staff person. The woman you pass on the way to the restroom in the restaurant could be that nurse in the hall. These residents are the people you’re protecting.

Be responsible. Protect the innocent and vulnerable. Wear your mask. Please.

(Names have been changed to be HIPAA compliant.

You May Also Like

Happy Birthday, Erin!

September 18, 2018

OCNJ

January 3, 2018

19 Comments

Denise

I love your blog! As always, so well written. You had me laughing & crying. And yes, I will wear a mask. ❤️👍🏽

marhiggins

Thank you, my dear. Miss you!

Lisa

Great post! You had me in tears!

marhiggins

Thank you, neighbor. Xoxo

Sarah Gooding

This was a great read- thank you so much

marhiggins

Thanks so much for reading!!

Ayesha Malik

Thank you for the work you do and for sharing your insight into a population so many of us don’t have the access to care for! It reminded me of the days I used to visit my father in a care facility. There are so many feelings that flow in that environment, but the prevailing one is of care and you have highlighted that in your blog. I look forward to reading more of your adventures in eye care!

marhiggins

Thank you for reading and your kind words. It makes me happy that your Dad received good care. Stay safe.

Kevin

I love your blogs, Maria. They are so honest, open and insightful, and revealing the human experience. But this one, hits so close to home. So much of it is my mother who is in a senior rehab facility in Florida. Her hallway is on lockdown and the nurses are there 24/7 to insure the best possible defense against someone bringing in the virus. Ma can be trying at times for the care givers and she needs to be held at other times. This post brought her closer to me. Thank you. 🙏🏽❤️🙏🏽

marhiggins

Your comment touched my heart. Thank you!! I hope you get to see your mother soon.

Rachel Dokholyan

I love this post. Your window into these homes is valuable. That quack quack mask actually looks comfortable!

marhiggins

The duck mask is the most comfortable of all I have tried! Thank you for commenting, friend!

Gail Cassidy

Maria, My first impression when I began reading was how “subdued” your words were. Then, after the “hug,” I had a difficult time reading as tears clouded my vision. You set the tone beautifully for meeting your patients, lightening up the tone with the duck mask and sharing the empathy any reader would feel for the Korean War vet and the variety of comments made by people who still want to be accepted or validated or recognized as a somebody. WOW!! Your beautifully described vignettes painted a clearer picture of the devastation we are going through than all the statistics we see daily on TV.

I get an email each week from news@mailer.thriveglobal.com asking for articles which she prints the following week. This one may exceed the word limit, but it sure would be worth a try to see if she would print it. She is part of a group led by Arianna Huffington, https://thriveglobal.com/authors/arianna-huffington.

You write so beautifully and with such great impactful meaning, it sure would be nice to have an even larger audience. Thanks for this beautiful piece.

marhiggins

Thank you for your kind words! I am glad that you enjoyed it. I will absolutely contact her! Thanks for the lead. Thanks for being ever supportive.

Kelly

Great blog, Maria. Sometimes we get so caught up in our own lives that we don’t even realize what others are going through. You displayed so many touching/sad stories here. I not only felt sad for the patients but for you as well.

marhiggins

Thank you for reading and commenting, Kelly! The stories are for sure sad, but the residents are surprisingly upbeat. They deal with everything so well. As for me, good or bad, right or wrong, when I am at work, I am somewhat immune. It was only when I sat down to write about it at home that the teary emotions flowed. Miss you. Xoxo

Lee Anne Mattucci

So beautifully written, Maria, as always. I feel nursing homes can be some of the saddest, but necessary places. I read that you said the patients are usually upbeat. Thank God for that. You are probably one of the reasons, even if the interaction is brief. I wear my mask for my own sake and those around me. Keep your blogs coming!

marhiggins

Thank you for always reading my blogs! Yes, some days hit harder than others, but the atmosphere now is one of open friendliness and acceptance of help. And chattiness. 🙂 xoxo

thediabeticsurvivor

Thanks for sharing this! Btw, I really need to try the duck masks.